Why I Think Funakoshi Sensei Would Approve

By Robert Johnson

Many years ago when I was a middle-aged Nidan (having started Karate in my early 30’s), I had the pleasure of assisting Aponte Sensei at the Claremont College Shotokan program. Along the way I met a young black belt from a Chicago Shotokan school. I recall him being a gifted practitioner and on the few occasions that we trained together I enjoyed learning from him. One evening Sensei asked me to teach the young man Chinese Hands set one. I’ve always been a fan of Sensei’s Chinese Hands as they incorporate flowing blocks to protect your center line while simultaneously attacking. Unfortunately my young friend felt otherwise and commented that he did not enjoy our program as it was not "pure Shotokan". I haven’t seen the young man since then, but his "pure Shotokan" comment stayed with me.

Eventually I was fortunate enough to test for Sandan and another comment came about that also stayed with me. At the end of the test Shihan Dean Pickard encouraged us all to, and I’m paraphrasing here, "go back to the beginning". I took that advice to heart and began to research the history of Shotokan. Along the way I stepped outside the Shotokan box and found new ideas that have made me a better martial artist. Thank you Shihan.

So what did I find? Well let’s have a look…

Pure Shotokan

How do we define Shotokan? Kihon (basics), Kata (forms) and Kumite (fighting). Techniques in kihon and kata are characterized by deep, long stances that strengthen the legs in an effort to promote stability and powerful movements. Linear movements followed by straight punches (oui-tsuki or gyaku-tsuki); hard blocks and snapping kicks (with the occasional yoko-geri kekomi) are taught in Kihon training and reinforced through kata. Kumite expands upon the lessons of Kihon, but sadly seems to have become divorced from kata due mostly to a lack of emphasis on self-defense in favor of tournament contests.

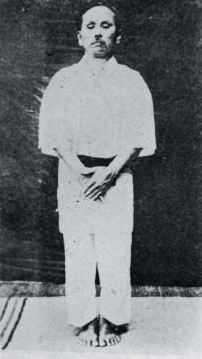

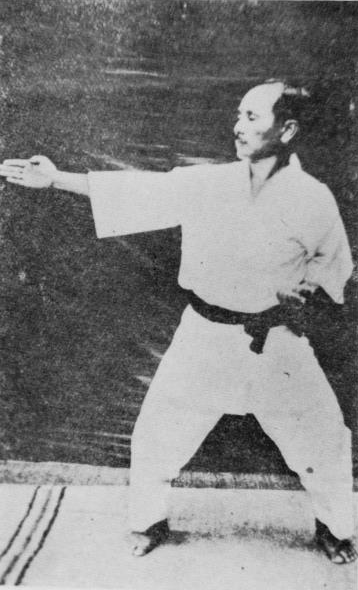

Clearly those deep, strong stances came to us from the old masters of Okinawa through Master Funakoshi, right? Well, maybe not. The photographs below of Master Funakoshi from his 1922 book Tote Jitsu show the stances before modern competition. Notice how high the three stances are compared to what we do today (photos on next page). 3

Jason Armstrong Sensei comments in his book, "A key point to note is that deep stances evolved with sports karate after the 1930’s, prior to this date stances in such arts as karate were predominately short and high."1 Armstrong Sensei’s medical analysis points to problems developed by deep stances that our Okinawan masters did not face, "Deeper stances reduce the ability to control lordosis, and if one attempts to maintain a "neutral spine" in deep stances hip rotation is actually lost…"2 He goes on, "To make matters more challenging for the lower back, practitioners take these deep stances which challenge posture and then perform impact oriented activities on wood floors involving lunging for punches and heavy landings after kicks. This can all take a toll on the spine/discs and surrounding soft tissue."3

As we moved further from the original intent of the art (self-defense and healthy longevity) towards the sport of Karate it seems that we may be doing more damage to ourselves than to our opponents.

This must mean that our kata are the "pure" Shotokan. Let’s look at a few.

Pinan (Heian)

The story goes that Master Itosu created the Pinan Katas to teach to school children, deriving the five Kata from the more complex Kanku-Dai and advanced Katas and removing the "dangerous" applications. Master Funakoshi learned the Pinan Katas from Master Itosu and, having made some modifications, renamed them "Heian"; a name with similar meaning but more acceptable to the Japanese mainland culture.

As is true with most stories, this may not be wholly accurate.

Choki Motobu Sensei (1871 – 1944), a contemporary of Master Funakoshi, notes that "As to the Pinan (5 Kata) the modern time warrior Mr. Itosu originated this style to use as teaching material for his students"4. I find it interesting that Motobu Sensei uses the word "style" to describe the Pinan Kata since "style" implies a defense system, as opposed to the commonly held belief that the Pinan Kata were simply exercises for 4

school children and beginners. According to Patrick McCarthy Sensei "Itosu established the Pinan in 1905"5 but they were "introduced into the school system in 1908"6. John Sells Sensei puts the introduction of the Pinan "from about 1902 to 1907"7. Clearly Master Itosu had been developing and teaching the Pinan Kata to his adult students well before it was "dummied down" to make it safe for children.

Assuming that the Pinan Kata’s were derived from the more advanced Kanku-Dai Kata, (which is not necessarily a safe assumption as I will soon discuss), it seems hard to believe that the "dangerous" applications had been removed. As Iain Abernathy Sensei notes: "The main difference between the adults’ and children’s training would simply be a matter of approach. The children would be taught the solo forms, without their applications, and would perform them as a form of group exercise; whereas, the adults would be taught the complete fighting system. As time has passed, it is the ‘children’s approach’ that has become the most widely practiced."8 My personal explorations of the Heian applications support Abernathy Sensei’s comments. All five Kata exhibit opportunities for groin attacks, knee strikes, joint locks, head butts, and throwing applications (see photo of Funakoshi Sensei executing a throw from Pinan Godan). Master Funakoshi himself stated, "Having mastered the five forms, one can be confident that he is able to defend himself competently in most situations."9

So are the Pinan Katas a derivation of Kanku-Dai and/or other advanced Shotokan Kata? Mark Bishop notes in his book Okinawan Karate that "Horoku Ishikawa of Shinpan Shiroma Shito-ryu typically came up with the theory that, ‘Itosu had based his five Pinan katas on an analysis of the kata Kusanku Dai’."10 (Kusanku Dai being the original name for Kanku-Dai). However, Mr. Bishop also notes that "Chozo Nakama told me that Itosu had learned the kata Chiang Nan from a Chinese who lived on Okinawa, and later remodeled and simplified this into five basic kata, calling them Pinan because the Chinese Chiang Nan was too difficult to pronounce…"11 The Chiang Nan theory is also noted by Patrick McCarthy in his book, Ancient Okinawan Karate. McCarthy Sensei notes that a Chinese man named Chan Nan (Chiang Nan) "had left a secret book on gongfu with Itosu, a book that allegedly influenced him significantly. Some say that this book was the Bubishi, which Mabuni had hand-copied and then published in 1934. Others say that it was a copy of Qi Jiguan’s 1561 Ji Xiao Xin Shu, a book from which came Itosu’s idea for the pinan kata."12 John Sells Sensei also supports the Channan theory in his book. 5

Students wishing to learn more on the relationship between the Pinan/Heian Kata and the Channan Kata should read Channan: Heart of the Heians by Elmar T. Schmeisser, Ph.D. Schmiesser Sensei’s analysis of the Channan Kata applications in relation to the Pinan/Heian kata brings new life to the lost meaning (at least as far as Shotokan is concerned) of these "basic" kata.

Before I leave this subject, I would like to bring up an interesting historical dilemma, namely; who taught Master Funakoshi the Pinan Kata? Master Funakoshi is himself quite clear that he learned the kata from Master Itosu, "Master Itosu, from whom I so gratefully learned the Heian, Tekki and other kata…"13. "Gima Shinkan also wrote that Funakoshi was so well known for teaching the pinan kata that many people referred to him as Pinan Sensei."14 However, the FAJKO (Federation of All-Japan Karate-do Organization) Karate-do directory states that "In 1919, at the age of fifty-one, Funakoshi Gichin, learned the pinan kata from Mabuni Kenwa."15

Granted this issue is more a historical curiosity than important event, but there is logic to the FAJKO’s statement. We know that Master Funakoshi was born and raised in the Shuri district, which is where he met and trained with Masters Azato & Itosu. We also know that he moved to Naha in 1891 and began training with other practitioners. (This may only be a four mile walk from Naha to Shuri, but with the responsibilities of family and career an eight mile daily commute on foot is a bit of a burden). Master Itosu created the Pinans in the 1900-1905 time-frames. Master Mabuni (1888 – 1952 founder of Shito Ryu) "was the original master of pinan…"16 And finally we know that Masters Mabuni and Funakoshi were close associates with a deep respect for one another. So it is not entirely unlikely that Master Funakoshi may have received initial training on the Pinan from Master Itosu while visiting Shuri and then refined his skills with Master Mabuni.

This investigation, albeit brief, confirms in my mind two things: first, the Heian Katas as we know them today have evolved from a more practical self-defense orientation to the current emphasis on competition "styling". This can be seen in the photos of Master Funakoshi performing the Pinan Katas in his 1922 book Tote Jitsu. Second, it is my belief that the Pinan/Heian Katas have much more to offer the Shotokan practitioner than simple exercise. Applications to these Katas should be explored by the advanced student and, in turn, taught to the beginning student as a means to defend him/herself. The Katas were intended to teach to beginners; I see no reason why the practical applications should be withheld until the student reaches the Yudansha level, or as is more typical, not taught at all. 6

Naihanchi/Tekki

Bushi Matsumura (1796-1893) is thought to have brought the Naihanchi Kata back from China, presumably from one of his trips to Fuzhou. The actual creator of the Kata is unknown; however it could well have been Matsumura himself. Matsumura was a legendary figure in Okinawa, acting as bodyguard and martial arts instructor to the King. A student of Tode Sakugawa (1733 – 1815), Matsumura went on to teach such legendary figures as Itosu Ankoh, Funakoshi Gichin, Mabuni Kenwa and Motobu Choki.

Several sources indicate that the Naihanchi Nidan & Sandan Katas were created by Master Itosu. Interestingly, Wikipedia notes that some researchers believe that it was originally one longer Kata broken down into smaller parts. The Wikipedia authors cite the change in the opening ready stances for Nidan & Sandan as support for this theory.

Regardless of what theory one chooses to believe, the three Naihanchi Kata were crucial to the studies of the great masters. Master Funakoshi notes in several books how he spent nine years studying the three Naihanchi before being allowed to move to a different Kata. "Before Heian was invented Tekki was the first kata for the Shorin ryu (fore-father of Shotokan) practitioners for many years."17 Choki Motobu found the kata so important that it was the only kata he passed on to his son, Chosei.18

The kata are usually described as being used for fighting on a bridge or against a wall. While this may be true, most researchers agree that the kata are intended to teach close-in fighting techniques that depend upon the ability to easily shift the body and rotate the upper body while maintaining a firm connection to the ground. My personal favorite theory comes from Bruce Clayton’s book, Shotokan Secrets. Sensei Clayton envisions Master Matsumura and Master Itosu, both members of the royal court and guards to the king, taking up stations on either side of the king, "There are two versions of the naihanchi kata (tekki shodan), credited to Matsumura and to Itosu, respectively. Itosu’s version opens by stepping to the right (Shotokan), as if stepping in front of the king from his left side. Matsumura’s version of the kata opens by stepping to the left (Isshinryu), as if protecting the king from his right side."19 It is easy to imagine these two highly skilled bodyguards closing ranks around their king.

Whatever the intent of the original Kata may have been, it was clearly important to the early practitioners that the applications be thoroughly understood; why else spend three years on each version? As Master Funakoshi tells us, the practice of "Te" was done in secret; hardly necessary if it was just a matter of getting the stance right or scoring a point. Also, the emphasis on "Do" was introduced to the art after it was accepted by the Japanese mainland, "The linking of Okinawan fighting arts and of Japanese karate-jutsu and karate-do to Buddhist religion or philosophy, especially Zen, is a modern innovation and one that is considerably newer than the systems it allegedly spiritually invigorates. In particular, the quasi-Buddhist teachings that are sometimes associated with Japanese karate-do are without foundation in the original form established by Funakoshi."20 It seems logical to assume that the applications to these Kata were being practiced diligently, unlike the "pure" Shotokan of today.

The photographs on the left show movements two and three from Tekki Shodan demonstrated by Master Funakoshi in his 1922 book Tote Jitsu. (Note: in his book it is referred to as Naihanchi Shodan).

The illustration to the right is an application (Bunkai) from the Saipai Kata of Goju-Ryu. Note the similarity with the Tekki Kata in these two movements. (Illustration from The Way of Kata by Lawrence Kane and Kris Wilder). 8

Why compare a Goju-Ryu application to a Shotokan Kata? Master Funakoshi shared his thoughts on the subject of differing schools, "There is no place in contemporary Karate-do for different schools."21 He explains further, "My belief is that all these "schools" should be amalgamated into one so that Karate-do may pursue an orderly and useful progress into man’s future".22 (Photo on left back row (l-r): Yasuhiro Konishi, Tatsuo Yamada, Front row (l-r): Chojun Miyagi, Gichin Funakoshi). (Photo on right: (l-r) Toyama Kanken, Ohtsuka Hironori, Shimoda Takeshi, Funakoshi Gichin, Motobu Choki, Mabuni Kenwa, Nakasone Genwa and Taira Shinken).

The concept of "pure" Shotokan does not fit Master Funakoshi’s concept of Karate-do.

Kushanku/Kanku Dai

Kanku Dai & Kanku Sho are referred to as "the living heart of Shotokan"23 by Bruce Clayton Sensei. Ironically, the young man who started my search for pure Shotokan also commented that he never bothered with this kata as it was ‘just the Heian’s put together’. It appears that nothing could be further from the truth.

The Kusanku (or Koshokun as Master Funakoshi referred to it in Tode Jitsu) kata was apparently created by Tode Sakugawa in honor of his teacher, a Chinese diplomat named Kusankun. The first known mention of Kusankun and his skills were recorded in the Oshima Hikki, a chronicle of the testimony of the officers and crew of a ship wreck in 1762. The witnesses recounted the impressive grappling techniques used by Kusankun, a man of small stature, to overcome a larger attacker. 24

Richard Kim Sensei tells us that a young Tode Sakugawa befriended Kusankun after having made a fool-hardy attack and ending up in a river. Kusankun was impressed with the young man and invited him to study with him in China, which he did for the next six years.25 Tode Sakugawa passed the kata to his student, Bushi Matsumura who in turn passed it on to Master Itosu. Master Itosu then created the "Sho" version of the kata.

Once again we have a kata that when observed through its historical origins proves to be something other than the traditional linear distance fighting of Shotokan. Instead we find a record of close-in grappling and striking. 9

As an interesting side note, the first series of moves (the arm movements that give rise to the name "To view the sky") have any number of bunkai. One comes from Master Funakoshi who indicates that the circular movement that ends with the hands together symbolizes that no weapons will be used (similar to the start of Tekki Shodan)26. My personal favorite is from John Sells Sensei, "in drawing the ‘circle’, one was really simulating the pulling of the topknot pin out of the hair, and then utilizing it as a dagger."27 Clearly fashion can be dangerous.

Further study

The remaining kata in the Shotokan curriculum all have equally interesting histories and I encourage everyone to do their own research. The student will find that these kata come from various sources, most originating in some form from China. Many of the kata from different styles share a common ancestor but have been modified either by the person first introducing the kata or by his students as they went their own way. Some of these changes came about simply because one student learned from the master when the master was young and nimble and another student learned the kata from the master as he and his kata matured.

Whatever the source of these kata’s may have been, one thing is clear in my mind; the masters of old were not tied to the absolute conformity that Shotokan practitioners strive for today. As Harry Cook Sensei stated, "One major difference between the way that karate kata were performed in the past and the way they are done now, is that in the past function dictated form, while in many of the modern versions, form dictates function. In the older versions the application of the technique was considered to be the most important aspect, while the modern approach to kata is to see the development of the outer form as paramount."28 The lack of real bunkai training in most Shotokan dojos is unfortunate and prevents the practitioner from being a well-rounded martial artist. Elmar T. Schmiesser Sensei, a former student the legendary Nishiyama Sensei said it best in his interview with The Shotokan Way:

"Shotokan" karate can be defined at least two ways, that of the testing curriculum, and that of the principles of movement. If you define the style by the testing curriculum, shotokan karate is worthless in the street. Street altercations start at 6 inches, generally involve a grab, and have no "yame." Standard shotokan karate is optimized in its testing curriculum for a duel between two essentially equal protagonists, using only percussive karate techniques pulled short of the target, aware of each other, on a smooth floor and using limited weapons, essentially empty-handed kendo. On the other hand, if you define shotokan karate 10

by the fundamental bases that underlie the generation of impact, the control of balance, the establishment of stance, the awareness of interval and the commitment of technique, then shotokan karate is eminently suited to developing the wherewithal to survive in the street, even if it is not a complete curriculum. Kata bunkai makes up the missing pieces, since they imply the aikido/judo fundamentals that cover the closer range aspect of the street fight."29

That is not to say that we should not strive for perfection in our kata, but rather we should also be mindful that kata transmits a history of fighting skill that we as martial artists should not ignore in our pursuit of perfection of character. We owe it to the masters of old to search for the essence of the kata rather than simply performing them in pursuit of trophies.

Kumite

Not much is said about kumite before the 1930’s. There are stories of the prowess of our progenitors: Bushi Matsumura’s contest with the stranded sailor Chinto that gave rise to our Gankaku kata; Master Itosu’s vice-like grip on the young ruffian who accosted him, or Matsumora Kosaku’s disarming of a samurai warrior with a wet towel, to name a few. However, while kumite as we know it today is rarely mentioned, it did exist.

Motobu Choki Sensei comments on two types of karate in his book, Okinawan Kempo. "The first part is basic movements taught to beginners. These basic movements are commonly called kata…The other is kumite and this may be compared to kime in Judo. The kumite is an actual fight using many styles of kata by grappling the opponent." He goes on to say, "The kumite or match has been practiced in the Ryu Kyu Islands from ancient days."30 This is confirmed by Mabuni Kenei, son of the great Mabuni Kenwa Sensei:

"In his younger days, many would challenge my father to a kake-damashi (a challenge match, or an exchange of techniques) after they had heard that he was practicing te. These challenges he would accept, and would choose a quiet corner of town to serve as the venue. There were no special dojo like there are today, so we used to train and fight upon open ground. There was no street lighting, so we had to use lanterns, and in the dim light the contestants fought. Each contestant would bring a ‘second’, and after a period the second would intervene and stop the fight. They would then declare a winner, and the one who needed more training. Such challenges were often made to my father, and he frequently acted as a second for others."31 11

Master Funakoshi may not have cared for the competitive nature of kumite; but it did not stop his contemporaries. During the 1920’s and 1930’s both Masters Mabuni Kenwa and Miyagi Chojun experimented with safety equipment (see photo of Master Mabuni in sparring gear). However, it should also be noted that these same men would come to express dismay over the competitive nature of karate after the 1930’s.

Weapons

Being a student of Matayoshi Kobudo Kodokan I would be remiss if I did not do a brief examination of weapons and Shotokan. A quick search on the internet will find photographs of Master Funakoshi using a bo and sai. In several of his books he mentions that his father was skilled in bo jutsu and that his instructor, Master Azato, was skilled in swordsmanship. Master Funakoshi also shared a mutual friend with Mabuni Kenwa, namely, Matayoshi Shinko the renowned weapon expert and fore-father of the weapon style that I study today. In fact, Masters Funakoshi and Matayoshi traveled to Kyoto in May 1917 where they demonstrated their arts.32 And finally one of Master Funakoshi’s own students in Japan became so enthralled with the weapons art that he is now regarded as the "father of Modern Kobudo"; none other than Taira Shinken Sensei.

So why don’t we study weapons in Shotokan? My research indicates that in order to convince the occupying Allied forces after World War II that karate was a peaceful art the decision was made to de-emphasize weapons. This certainly makes sense, but I believe the time has come to re-introduce a few weapons kata in the Shotokan program. Judging from the number of Shotokan practitioners that I have met at Sanguinetti Franco Sensei’s Matayoshi Kobudo Kodokan International this may well be happening. 12

Where has this research led me?

The historical data indicates to me that we have strayed too far from the original intent of our art. That is not to say that I completely disagree with the competitive nature of Shotokan. Tournament sparring and tournament kata are great formats to build confidence, especially in our youth. However, if we hold ourselves out as teaching self-defense are we being truthful? Does scoring a point in a tournament really translate to having a glass bottle jabbed in our face? Maybe it does for those skilled natural athletes, but what about Minnie and Joe Six-pack that walked in the door to learn how to defend themselves on the street? I strongly believe that Shotokan contains all the necessary skills, but they have been forgotten. It is my personal goal to regain what has been lost.

The reality is that it’s not that hard. Our kata contain the principles necessary if we put them into context of the most likely attack scenarios. Patrick McCarthy Sensei refers to these as the Habitual Acts of Physical Violence and lists 32 different scenarios. Jason Armstrong Sensei lists the top ten most likely attacks gathered from hospital data. Based upon this information, along with attending seminars; watching videos; training in other arts; and just having the good fortune of training with people like Aponte Sensei and Sanguinetti Sensei, I have developed a two person Heian Bunkai Oyo (application of kata principles) Flow Drill that utilizes the moves we all know from the five Heian’s, but puts them into a more realistic attack/response scenario. The ultimate goal is to flow through these movements in a rapid, close-in attack/defense drill, as opposed to the static, unrealistic bunkai that we’ve seen in the JKA videos. Eventually I hope to do the same with the Tekki and other katas.

As an aside, I am not alone in my disdain for the JKA bunkai video series. Kousaku Yokota Sensei, 8th Dan and former member of the JKA for 40 years, devotes an entire chapter in his book Shotokan Myths to this subject. In it he describes how the series was created in the 1980’s in response to the western students asking questions, something that is not done in a Japanese dojo. "The problem is that they disregarded or dropped the true applications that are either hidden or modified movements in the kata."33 He goes on, "Do not blame your techniques if you have problems as the ma-ai (distance) and applications aren’t realistic or applicable." 34 Strong words indeed.

Please don’t get me wrong, I love Shotokan. I love the deep stances, despite the aches and pains they’ve caused, and I love trying to perfect my kata and kihon; however, I believe that there is an important part of Shotokan that is being ignored. 13

Conclusion

My Shotokan may not be "pure"; (whatever that may mean), but, from what I’ve found, neither was Master Funakoshi’s. My Shotokan is the result of having had the incredible luck to walk into a dojo lead by an instructor (Ty Aponte Sensei) who has true martial spirit and, as Master Funakoshi described his instructors Masters Itosu and Azato, does not suffer from petty jealousy. Because of Aponte Sensei, My Shotokan has been opened to other ideas by incredible instructors like Sanguinetti Franco Sensei who along with teaching me Matayoshi Kobudo Kodokan has also shared concepts from his style of Goju-ryu; Mike Kazmer Sensei and his sempai’s Buddy Merritt and Tim Richmond from the Araki-Mujinsai-Ryu school of Iaido; and Mike Whiteside Sensei, whose solid grounding in Shotokan keeps me anchored to the tradition.

As Master Funakoshi noted, "Because karate eventually takes on a deeply personal character, it may be said that every karate-ka has his own karate." I have much to learn, but I do believe that impure as it may be, My Shotokan has become My Karate.

Robert Johnson

February 2013

References

1 Street Fighting Statistics & Medical Outcomes linked to Karate & Bunkai Selection 2nd edition 2012 Jason Armstrong pg. 109

2 Ibid pg. 109

3 Ibid pg. 109

4 Choki Motobu Okinawan Kempo ed. Annette Hellingrath (Masters Publication first published 1926), 26.

5 Patrick McCarthy, Yuriko McCarthy, Ancient Okinawan Martial Arts: Koryu Uchinada: Vol. 2, (Dec 2011) pg. 12

6 Ibid pg. 15

7 John Sells, Unante The Secrets of Karate 2nd edition (2000) pg. 257

8 Iain Abernathy The Pinan / Heian Series as a Fighting System; http://www.iainabernethy.co.uk/article/pinan-heian-series-fighting-system-part-one ,pg. 1

9 Gichin Funakoshi, Karate-Do Kyohan, Kodansha Intl, pg. 35

10 Mark Bishop, Okinawan Karate, Tuttle publishing, 1999, page 89

11 Ibid Bishop page 88

12 Patrick McCarthy, Ancient Okinawan Karate, page 12

13 Gichin Funakoshi, Karate-Do Nyumon, Kodansha Int’l, page 22

14 McCarthy, Ancient Okinawan Karate page 12

15 Ibid McCarthy pages 12-13.

16 Ibid McCarthy page 12

17 Kousaku Yokota, Shotokan Myths, XLibris, 2010, pg. 138

18 A Meeting with Chosei Motobu by Graham Noble http://seinenkai.com/articles/noble/noble-motobu2.html, page 2

19 Bruce D. Clayton, PhD., Shotokan Secrets, Ohara Publications, 2010, pg. 169

20 Donn F. Draeger, Modern Bujutsu & Budo Vol. 3, Weatherhill, 1974 pg. 128

21 Gichin Funakoshi, Karate-Do My Way of Life, Kodansha Int’l., pg. 38

22 Ibid page 38-39

23 Bruce Clayton, Shotokan Secrets, pg. 73

24 Patrick McCarthy, The Bubishi, Tuttle Publishing, 2008, pg. 69;

25 Richard Kim, The Weaponless Warriors, Ohara Publications, 1978, pg. 21

26 Gichin Funakoshi, To-te Jitsu, Masters Publications, 1922, pg. 140

27 John Sells, Unante pg. 265

28 Harry Cook, Throws and Locks in Karate Kata, http://www.theshotokanway.com/throwsandlocks.html

29 Interview with Elmar T. Schmiesser http://www.theshotokanway.com/elmarschmeisserinterview.html

30 Choki Motobu, Okinawan Kempo, May 1926 pg. 37

31 Patrick McCarthy, Ancient Okinawan Martial Arts: Koryu Uchinada: Vol. 2, Dec 2011, Pg. 5

32 Patrick McCarthy, Koryu Uchinada page 9

33 Kousaku Yokota, Shotokan Myths pg. 96

34 Ibid pg. 97